Author Archives: Estelle Tang

Farewell, MWF 2011

As we decamp from Beer Deluxe, accept that no, we can’t live in the magnificent BMW Edge, and unplug our laptops from ACMI powerpoints, I have to admit it’s nice to have some breathing space and an opportunity to reflect on another brilliant MWF.

Of course, there were some low points. For example, when the MWF team thought up the theme ‘Stories Unbound’, I’m pretty sure they didn’t mean that I should accost festival guests with questionable snippets of my life experience every time I had a wine (or eight). Plus, the usual festival dashing about meant that I didn’t catch all the sessions I wanted to; despite daily trying to one-up festival director Steve Grimwade in terms of how many I managed to see, I had to lie to beat him.

But I am always energised when I reflect upon MWF events, and my memories from the past eleven days provide no exception. Here are my 2011 festival highlights, in no particular order:

1. Peggy Frew’s reading at the launch of The Big Issue fiction edition. Like a lot of festival punters, I’m often in two minds about readings, but when Frew finished reading from her Big Issue story, ‘Camping’, you could hear the audience collectively, finally exhale.

2. Speaking with debut and early-career novelists Melanie Joosten, Jessica Au, SJ Finn and Raphael Brous about love, growing up, work and ghosts in Melbourne’s New Wave

3. The passionate and incendiary Mona Eltahawy on the uprising in Egypt and how it was inspired by and will influence the politics of the Middle East

4. Engaging in a bit of Julia Zemiro-love at Friday Night Live

5. The modest but utterly original César Aira discussing his slim novels and his unusual no-editing, ‘flight forward’ technique

While all these experiences are defined by having been part of MWF 2011, they are also springboards that will propel me into directed and engaged reading for the rest of the year and beyond.

As always, my thanks to the MWF team for an inspiring, varied, well-run and exciting festival. And this year, a guernsey too to Melbourne weather, which was mostly salutary, mostly kind.

What were your highlights from MWF 2011?

Switching to Fiction: Christopher Kremmer, Anna Funder, Leslie Cannold and Malcolm Knox

When Christopher Kremmer fled from an op shop where he’d found a bound collection of old Sydney Morning Herald newspapers from the period when his father had been a jockey in the Melbourne Cup, he realised that his ‘whole life was about running away from the past’. This time, he decided to turn back around and face it, and was drawn into the stories of the horseracing world. His novel The Chase tells the story of a scientist, Jean Campbell, trying to root out drug use in the horse racing industry. Even for the experienced non-fiction writer and journalist, research was nigh impossible: ‘the world of horseracing is a world of secrets … it’s all about masking what goes on to increase the odds’. To make his task even more complicated, the real-life scientist Kremmer was basing Campbell on had never left any records.

When Christopher Kremmer fled from an op shop where he’d found a bound collection of old Sydney Morning Herald newspapers from the period when his father had been a jockey in the Melbourne Cup, he realised that his ‘whole life was about running away from the past’. This time, he decided to turn back around and face it, and was drawn into the stories of the horseracing world. His novel The Chase tells the story of a scientist, Jean Campbell, trying to root out drug use in the horse racing industry. Even for the experienced non-fiction writer and journalist, research was nigh impossible: ‘the world of horseracing is a world of secrets … it’s all about masking what goes on to increase the odds’. To make his task even more complicated, the real-life scientist Kremmer was basing Campbell on had never left any records.

Then there’s the balancing act between a non-fiction writer’s research instinct and the novelist’s creative impulse: ‘You overresearch it, but you get to a point where you need to let go of those real people. Once you start doing that you start to be able to pour yourself into these character.’

Chair Geordie Williamson asked whether there was any pressure on Anna Funder to follow up her acclaimed account of the former East Germany, Stasiland, with something in a similar vein? ‘My husband said I had second-album syndrome, which I don’t think is true,’ said Funder of her new novel, All That I Am.

In non-fiction, Funder believes, it’s important to honour the people you’re writing about, so in Stasiland, for which she spoke with people whose courage had been ‘almost unbelievable’, she wanted to pay tribute to that. With All That I Am, though, the people on which Funder based her characters are no longer alive, and what happened isn’t known, so ‘I looked at shards of history and put together a plot which I think is the most likely thing that happened’. While this lack of material might seem less advantageous, there is an upside: ‘The biggest moral limit of non-fiction is not being able to represent the consciousness of your characters from the inside. That was a huge liberation.’

with people whose courage had been ‘almost unbelievable’, she wanted to pay tribute to that. With All That I Am, though, the people on which Funder based her characters are no longer alive, and what happened isn’t known, so ‘I looked at shards of history and put together a plot which I think is the most likely thing that happened’. While this lack of material might seem less advantageous, there is an upside: ‘The biggest moral limit of non-fiction is not being able to represent the consciousness of your characters from the inside. That was a huge liberation.’

Leslie Cannold ‘didn’t make a conscious choice to write a novel’. The impetus for writing The Book of Rachael was a BBC documentary attempting to unearth historical truths about the life of Jesus. Cannold ‘started wondering what my family were up to’ at this time – but it became clear that the historical record was not concerned with women. Fronting up to the library, Cannold demanded everything that existed on Jesus’s sisters, but she was told there was basically no existing material on the subject. Cannold decided it would be her responsibility to tell such a story.

Where fiction and non-fiction do mix, suggested Malcolm Knox, was ghostwriting. Someone like the famously laconic Bart Cummings is hard to write a 300-page book about, so the tools of fiction can assist in creating a narrative. Yet there is a point at which you have to stop and go no further – you can’t make anything up. In regard to Knox’s novel The Life, there was at least one good reason not to write a biography of surfer Michael Peterson – one had already been written. But he ‘was always about 50 per cent fiction anyway’, said Knox.

All the guests thought of fiction as serving a different purpose to non-fiction in telling a story. Cannold thought that if she wanted to write about something about which there was very little known, she would elect to use fiction. Kremmer thought that, for his next book, he would probably be returning to the more familiar ground of non-fiction, but not because fiction was unsatisfying: ‘I found it one of the great experiences of my writing career’.

The Connected Book: what are the possibilities?

Now that we’ve accepted the ereader, it’s time to look at some of the creative possibilities afforded by digital texts. Publisher of Booksquare.com, Kassia Krozser; author of digital fiction Inanimate Alice and Flight Paths, Kate Pullinger; founder of audio digital library LibriVox, Hugh McGuire; and if:book’s Simon Groth this evening discussed what multilayered media, text enriched with images, sound and interactive features might soon do to revolutionise a bookshelf near you.

What exactly do digital texts offer? Screen-based formats allow for so much more than just reflowable text, Groth said in his introduction, which alone is a huge leap from the print workflow; even the humble hyperlink has the potential to change reading. And then there’s ‘networking to other texts, augmentation through images and other media: a book is not a petri dish, it’s a living thing connected to a wider community’. But how do we capture all the facets of this connection?

To answer this question, Groth asked another. How did Pullinger’s networked novels first come about? In thinking about new forms of writing online, she spent a year thinking about what it meant to put a story on a screen – what that opened up for storytelling. She’s continued to write traditional forms such as short stories, but although Inanimate Alice and Flight Paths both have text at their hearts, they also use music, images and games to tell stories. But is this still a ‘reading’ experience? Groth agreed that it was reading, but perhaps enhanced reading – not gaming, or any other activity.

And how exactly do you publish these digital texts? McGuire started LibriVox in 2005. The website brings readers and listeners together from around the world to publish user-recorded audio of public domain books. In doing this, McGuire said, he’d created a publishing entity that ‘broke every rule’ – they’ve got no quality control process, for example. But it’s extremely productive: around 100 books a month. After that project he thought about how you would create a text publisher that suited the online climate, and he came up with Pressbooks, which is still in its testing phase. Pressbooks uses a blogging platform, WordPress. What was the logic behind this? ‘There’s no technical difference between blogging and writing a book, though the thought process is obviously very different.’

And how exactly do you publish these digital texts? McGuire started LibriVox in 2005. The website brings readers and listeners together from around the world to publish user-recorded audio of public domain books. In doing this, McGuire said, he’d created a publishing entity that ‘broke every rule’ – they’ve got no quality control process, for example. But it’s extremely productive: around 100 books a month. After that project he thought about how you would create a text publisher that suited the online climate, and he came up with Pressbooks, which is still in its testing phase. Pressbooks uses a blogging platform, WordPress. What was the logic behind this? ‘There’s no technical difference between blogging and writing a book, though the thought process is obviously very different.’

The discussion of these new platforms and user-created content raised the question of what is publishing, and who are publishers? For Kroszer, this depends on how you define a book; a blog, for example, is more like a newspaper or a magazine than a book. Bloggers and readers of blogs might agree that some blog pieces aren’t crafted enough to warrant the process of publishing, marketing, reproducing and distributing. Kroszer though that perhaps pulling some blog posts out and creating a compendium of them would be worth doing if the particular pieces would stand the test of time.

The connected book, though, might be more than just the object or location of text online. Authors can connect with readers in a much more immediate way through social media, Pullinger has found. For example, smartphones can allow you to interact with a story in new ways depending on your location.

McGuire thought that though the core text of what we call a book today might still exist in a particular place on the web – ebooks still look like books, after all – but we will see layers of response to this text, through comments and other reader-generated interactions. The book will be central, core thing, but engagement will compile around and on top of that.

Kroszer was excited by this: ‘You’re making me question the definition of a book!’ She thought that this is a question that  everyone in publishing is struggling with. Think of a cookbook: though you might love the idea of a print book with beautiful pictures of the end product, you might want to take an ingredient list to the supermarket. On top of this, readers might want to rate recipes – connect to others’ interpretations of the content.

everyone in publishing is struggling with. Think of a cookbook: though you might love the idea of a print book with beautiful pictures of the end product, you might want to take an ingredient list to the supermarket. On top of this, readers might want to rate recipes – connect to others’ interpretations of the content.

There were many considered questions from the audience, including one pertaining to new terms for a ‘book’ and even for ‘reading’ – are these nouns appropriate for connected interaction with content? McGuire cheerily joked that even the word ‘content’ was fraught – in some quarters, people ‘will kill you if you describe it as “content” rather than as some kind of sacred text.’

But what do you think? Is ‘book’ going to continue to be a useful term? What about ‘reading’?

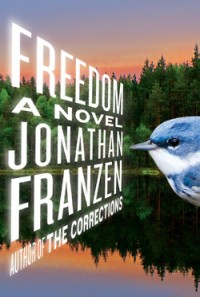

Birds don’t have to be for anything: Jonathan Franzen and Sean Dooley on birds

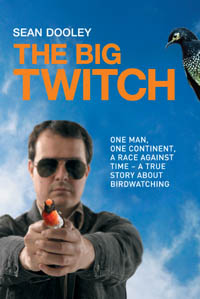

Jonathan Franzen is a renowned bird-watcher and conservationist, as is Sean Dooley (The Big Twitch). They spoke this afternoon to ABC Radio’s Michael Veitch (himself a keen bird-watcher) about their mutual passion. Is there something about the elusiveness of birds that attracts writers?

Jonathan Franzen is a renowned bird-watcher and conservationist, as is Sean Dooley (The Big Twitch). They spoke this afternoon to ABC Radio’s Michael Veitch (himself a keen bird-watcher) about their mutual passion. Is there something about the elusiveness of birds that attracts writers?

To kick off, Veitch polled audience members, who mostly proved at least either bird-watchers or Franzen/Dooley readers, if not a combination of both. For fairness’ sake, Veitch also asked ‘How many of you are bird watchers who have never heard of Jonathan Franzen or Sean Dooley?’ Two lone but brazen birders put their hands up and received an air-kiss from Franzen in response.

Audience bona fides having been ascertained, it was time to test the panellists, who went to the Werribee sewage farm yesterday (which Franzen called ‘one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been’). Veitch reeled off a list of Victorian birds, and it turned out the intrepid travellers hadn’t seen very many (one particular species had been sighted ‘very distantly, through heat shimmers’, but Franzen joked ‘Yes, we missed almost everything’) even though the site is renowned for its birdlife: ‘25 kilometres of open poo ponds’ that Dooley said birds love. Apparently 370 species of birds have been sighted there in the past fifty years or so.

Writing is an isolating pastime, but, Veitch asked, is birding something you can enjoy doing with others? ‘More eyes means you see more stuff’, Franzen agreed, but it can also be done alone; ‘I prefer to be myself. It’s a great, great activity … who wants to go to a party when you can slip out and see a bird or two?’ Indeed, those hoping to see Franzen at MWF parties may be disappointed, as Dooley then happened to mention there was somewhere near Federation Square where they could slip out to see some avian life instead.

Dooley agreed: ‘I basically go bird-watching for the birds, not for the bird-watchers.’ Not surprising from someone who blew his inheritance on buying a four-wheel drive and bird-watching for a year, an experience he wrote about in The Big Twitch: ‘It was a good chance to get out into nature.’

Dooley agreed: ‘I basically go bird-watching for the birds, not for the bird-watchers.’ Not surprising from someone who blew his inheritance on buying a four-wheel drive and bird-watching for a year, an experience he wrote about in The Big Twitch: ‘It was a good chance to get out into nature.’

Not only is it a chance to reconnect with nature, but bird-watching is also a pursuit that has changed the way Franzen responds to nature. Instead of approaching it as something that’s for him, for his contemplation – ‘Am I alone enough?’ – it’s now the habitat of the creatures he loves.

Do the writers write differently thanks to their interest in birds? Franzen: ‘More carefully … As a reader I turn off if I’m about to be subjected to too much appreciation of nature.’

Then to the cerulean warbler, the bird made arguably a thousand times more famous by its inclusion in Franzen’s latest novel, Freedom. Why did he decide to feature this bird, a ‘bluish, small and unintelligent looking’ one? ‘It’s arguably the fastest declining songbird in North America,’ Franzen explained, ‘and happens to have a stronghold in West Virginia’, where the novel is set. That location is ‘a dystopian vision of what America is becoming’, with the environmental destruction, out-of-town interested making money, and residents maintaining a relatively low quality of life. ‘It’s a pan-American bird,’ which winters in South America, and ‘it’s pretty’.

Veitch had purposely avoided asking his guests why birding was such an important pursuit for them, but by session’s end, Franzen had kind of answered it anyway: ‘I feel like it’s good to have something to do for my own sake – I have a Protestant work ethic that I can’t get away from except when I fall into a bird-watching trance.’ He’s become involved in bird conservation ‘as a way of justifying post hoc these days I spend for no other reason out in the bush other than it brings me pleasure’. Nevertheless, this doesn’t detract from the fact that birds are beloved and interesting qua birds: ‘Birds don’t have to be for anything.’

New News: Innovation in Journalism – what might it look like?

The time is ripe for change and innovation in journalism, with the proliferation of new technology, information sourcing devices constantly at punters’ fingertips and widely publicised missteps by media behemoths. David Higgins, News Limited’s innovations editor, Sam Doust, ABC Innovation,’s creative director and Jay Rosen, New York University joined Margaret Simons to discuss their ideas on how to innovate in journalism.

Where did the idea for this session come from? When writing a story on the future of Fairfax for The Monthly, Simons asked a senior executive how they were going to innovate journalism, the interviewee said ‘What do you mean’? Although the media is changing quickly, the core of the journalistic method hasn’t changed very much since printing press was invented; Simons argued that no other industry can say the core product has stayed so constant.

Where did the idea for this session come from? When writing a story on the future of Fairfax for The Monthly, Simons asked a senior executive how they were going to innovate journalism, the interviewee said ‘What do you mean’? Although the media is changing quickly, the core of the journalistic method hasn’t changed very much since printing press was invented; Simons argued that no other industry can say the core product has stayed so constant.

Is it possible to change the way we tell stories or communicate news? Higgins suggested that it’s possible to vary the presentation of news and reach different audiences through ‘gamification’. During his tenure as website editor for the Sydney Morning Herald and news.com.au, fighting in Sudan was intensifying, yet he ‘couldn’t get people to read these stories no matter how good the journalism was’. MTV, of all outlets, said Higgins, came up with an idea that cut through this – a computer game called Darfur is Dying. The difference between this method of storytelling and how a journalist or foreign correspondent would tell the story was startling, and Higgins stressed that he wasn’t suggesting games as the new face of journalism, but one ‘attempt to get a level of differentiation into journalism – why we’re suffering is there’s so many similar versions of the same stories out there’.

Sam Doust took to the projector to demonstrate some of the new presentation and marketing ideas the ABC is using to showcase its work. Their The Explainer tumblr contains many of these examples. For instance, to complement the Rear Vision radio program on how to get out of Guantanamo Bay, an interactive flash and html animation was created. This was just one way to reach people who might not beading the articles; the Journey through Climate History moving timeline is a visually engaging interface for engaging with the information itself, which, Doust said was of course more important than any visualisation technique.

Jay Rosen agreed with this, saying that innovation doesn’t necessarily involve building new tools or programming machines: ‘The tools I’m interested in are people, ideas, and the will to do things differently’. Rosen called this ‘soft’ innovation – changing the way you do journalism, which often uses new tools but isn’t strictly about that. What kinds of innovations would involve readers working with journalists (‘mutualisation’ in Rosen’s parlance)? Take a look at openfile.ca – anyone who wants to can ‘open a file’; that is, prompt an investigation. Editors then assign a story to a reporter. Stories that come up through this method are five to seven times more visited than those their editors suggested. Another way to do this is covered in Rosen’s blog post, The 100 Percent Solution: decide on what you want to cover, and work out how to cover all of it. How exactly could you do this? Deputise your users in, for example, tweeting comments, scores and images.

Many of the audience members either took this advice to heart or didn’t need it: the #newnews hashtag was getting a thorough workout, with heads bent over smartphones and fingers tapping away on laptops throughout the session.

Meg Vann: ‘The writer’s journey is a long one’

While a book is an accessible, concrete object, the process of creating a book is somewhat more mysterious. To help bring it into the open, MWF is devoting a whole-day event to how books are created. A Book’s Journey brings together publishers, editors, writers and other industry guests to shine the light on the publishing process.

One of these guests, Meg Vann, manages The Australian Writer’s Marketplace for Queensland Writers Centre, and tutors creative writing. Her first book, a light-hearted thriller, is under consideration with an Australian publisher. We asked Meg about her part in a book’s journey.

Meg, you manage the Australian Writer’s Marketplace (Queensland Writers Centre). Where does this organisation (and others like it around Australia) come into a book’s journey? What kind of assistance can it provide?

AWM was originally developed as a resource to help emerging writers find marketplaces to send their work – it started out in the nineties, basically as a Yellow Pages for writers. Now it is both a book and a website, and it also includes information and services for all writers – whether someone is brand new to writing, an established author writing to contract, or anywhere in between, there is something in AWM or AWMonline for you!

There are some quintessential problems that spring up for new writers: lack of inspiration, time, or honest, useful feedback. Are there any new trends, though, in what writers need or seek? Have the internet and digital resources helped writers (or hindered them)?

The online environment is vital for writers to connect with each other, and with audiences. But it can be a real time vampire, too, so you have to set clear limits! AWMonline runs a regular Writing Race on Tuesday nights. It is a one-hour online forum that is freely available to all writers where you can chat with fellow writers (including some very special guests) to provide motivation, accountability and feedback. Some of our regular Racers have gone from beginners through to winning competitions and getting published!

You’ve said that you love your day job, which ‘involves schmoozing at awesome writers’ festivals’ (thanks!) Why are contacts in the publishing industry important for writers polishing their craft or trying to get published?

The wonderful literary agent Sophie Hamley calls publishing ‘an industry of relationships’ and it is so true! Meeting other writers – as well as publishers, editors, agents, booksellers, and all the other industry folks – is so important when it comes to developing your understanding of professional standards and where your work sits within the broader marketplace. I always encourage people to just be themselves when schmoozing – but to be their best selves: ready to speak briefly and engagingly about their work when asked, and always courteous and curious about everyone you meet.

You’re also a graduate of a writing and publishing course at the University of Queensland, with a novel manuscript of your own. How has your two-sides-of-the fence experience helped you in putting together your manuscript?

Working in the industry has helped me focus more on my writing, and given me many wonderful opportunities to meet other writers. Australia is blessed with a generous and supportive literary culture – I feel enormously fortunate to work in a role where I can ‘give back’ to other writers, as well as talk constantly about books and writing! Being immersed in the industry as well as immersed in my own writing has made me so much more aware of both the craft and the business aspects of this thing that I have loved so much all my life: creative writing.

How would you describe the writer’s journey?

The writer’s journey is a long one. An actor friend advised me once that any career in the arts is like a never-ending bus ride – as long as you stay on the bus, you’ll get somewhere, even if it wasn’t where you originally planned to go!

Catch Meg in A Book’s Journey (tickets for Part 1 and Part 2 still available) on Saturday 27 August.

Blogger’s picks for MWF 2011

I’ve started circling events in the MWF program. Terrifying and all-encompassing though the red pen carnage may seem, there are some events I know I won’t miss.

Usually my list is fiction-heavy, but thanks to the growing hubbub about digital news and the recent resurgence in interest about the ethics of journalism, New News 2011 has been a focus of my festival planning this year. New News 2011 will bring together media leaders and commentators from all over Australia and the world, including New York University media critic Jay Rosen, chair of the Public Interest Journalism Foundation Margaret Simons, and ABC Managing Director Mark Scott. Rosen’s Big Ideas: Why Political Coverage is Broken promises electrifying analysis of journalism today, and Media Leaders Held to Account offers one intrepid participant the opportunity to share the stage with Mark Scott and Crikey‘s Sophie Black (to be in the running, submit a question at OurSay).

Usually my list is fiction-heavy, but thanks to the growing hubbub about digital news and the recent resurgence in interest about the ethics of journalism, New News 2011 has been a focus of my festival planning this year. New News 2011 will bring together media leaders and commentators from all over Australia and the world, including New York University media critic Jay Rosen, chair of the Public Interest Journalism Foundation Margaret Simons, and ABC Managing Director Mark Scott. Rosen’s Big Ideas: Why Political Coverage is Broken promises electrifying analysis of journalism today, and Media Leaders Held to Account offers one intrepid participant the opportunity to share the stage with Mark Scott and Crikey‘s Sophie Black (to be in the running, submit a question at OurSay).

One fiction writer who has raced up my list of to-sees is Steve Hely, whose How I Became a Famous Novelist is a magnificently titter-inducing work of satire. The novel tells the story of a down-and-out college entrance essay writer who cracks the code of the best-selling literary novel (‘Rule 16: Include plant names’). As well as being a novelist, Hely writes for television programs 30 Rock, The Office and American Dad, and it shows in his mortifyingly acute descriptions (‘The only other customer at the coffee bar…was tearing apart a cranberry-raisin muffin with frantic violence. Crumbs were strewn across her open copy of The Jane Austen Women’s Investigators’ Club.’) Not for reading die-hards who cannot laugh at themselves. Hely is appearing in TV Tales, with Wendy Harmer, Tim Ferguson and many more TV writers; The Morning Read, always a lovely way to ease yourself into festival season; The Comedy of Publishing, and Friday Night Live.

titter-inducing work of satire. The novel tells the story of a down-and-out college entrance essay writer who cracks the code of the best-selling literary novel (‘Rule 16: Include plant names’). As well as being a novelist, Hely writes for television programs 30 Rock, The Office and American Dad, and it shows in his mortifyingly acute descriptions (‘The only other customer at the coffee bar…was tearing apart a cranberry-raisin muffin with frantic violence. Crumbs were strewn across her open copy of The Jane Austen Women’s Investigators’ Club.’) Not for reading die-hards who cannot laugh at themselves. Hely is appearing in TV Tales, with Wendy Harmer, Tim Ferguson and many more TV writers; The Morning Read, always a lovely way to ease yourself into festival season; The Comedy of Publishing, and Friday Night Live.

Finally, the world has been keeping a close eye on the Middle East this year, with a chain of political upheavals generating debate, concern and hope. As Egyptian commentator and journalist Mona Eltahawy has said, ‘Tunisia allowed us to imagine a future beyond our dictators. And everybody was watching Tunisia. And then everybody started watching Egypt and then Bahrain and Yemen and Libya and Syria. So, everybody’s paying attention.’ I’m looking forward to Eltahawy’s analysis in Big Ideas: The Roots of the Egyptian Revolution – From Tahrir Square to Liberation From Dictatorship. You can see Eltahawy commenting on the trial of Hosni Mubarak here, and on the Syrian blogger hoax here.

What are your festival picks?