Blog Archives

MWF 2010 authors on… listening

Posted by Angela Meyer (LiteraryMinded)

I’ve given MWF guests a list of 15 random topics to respond to. The idea is to entertain and introduce you, the reader, to other sides of the MWF authors and their work, which may not be revealed on festival panels. The authors were allowed to respond in any way they liked, and were given no word limits. To learn more about the authors and what they’re doing at the festival, click their names through to their MWF bios.

The film Morvern Callar by Lynne Ramsay is based on a book by Alan Warner (although the film has a completely different tone and aesthetic). The title character is a young woman whose boyfriend has committed suicide as the film opens, leaving behind the manuscript of a novel, which Morvern then submits to publishers under her own name, successfully, as it eventually turns out.

This is the final scene. It may not be apparent that Morvern is actually wearing earphones connected to a Walkman (this is pre-iPod), which provides an implied diegetic source for the soundtrack, even if the version we hear is obviously overdubbed. This theory is subsequently confirmed by the final few seconds of the clip, in which the sound is ‘overheard’ through earphones turned up too loud, although by that point there is no accompanying image, so that the sound only becomes literally diegetic after it has ceased to make sense in diegetic terms.

Clearly there is something else at stake besides narrative logic by the time we get to the black screen.

I remember going to a concert with friends when I was a teenager, when one of our group also insisted on wearing a Walkman, through which he listened to heavy metal, to register his disgust at the sappy Christian folk being performed on stage. This has always struck me as a peculiarly eloquent and perverse gesture, which expresses both the need to belong to a group and the inability to reconcile oneself to that need. I think that this same gesture, whose perversity goes unremarked in the clip, except insofar as its eloquence is amplified by the sound design, means something more in Morvern Callar.

The sequence also works visually of course. It is not merely moving bodies filmed under a strobe. Rather, it is a tour-de-force of choreography and editing, in which a series of jump cuts disguise abrupt focal shifts as well as changes in the lighting.

DEDICATED TO THE ONE I LOVE.

David Bowie. Preferably Hunky Dory, Pin Ups or The Man Who Sold the World.

We talk a great deal in Australia about the ‘right’ to free speech. Much less is said about the right to be heard, to be listened to. Susan Bickford has interesting things to say about this in The dissonance of democracy: listening, conflict and citizenship (Cornell University Press 1996). In my own work (with Joan Eveline) I’ve been exploring the concept of ‘deep listening’, developed among transcultural mental health practitioners (Gabb and McDermott 2007: 5), who describe deep listening as entailing ‘an obligation to contemplate in real time, everything that you hear – to self-reflect as you listen, and then, tellingly, to act on what you’ve registered’. These ideas and references can be pursued in Mainstreaming Politics (Bacchi and Eveline, University of Adelaide Press, 2010), available as a free download at http://www.adelaide.edu.au/press.

Angela says…

Feel free to share your own responses to the topic, or to the authors’ responses, in the comments.

MWF 2010 authors on… their first computer

Posted by Angela Meyer (LiteraryMinded)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macintosh_Classic

She was a first gen Mac, I was but a starry-eyed Year Eight student.

We got to touch for thirty minutes a week. Mostly awkward fumbles with a square mouse playing Minesweeper while humming Go West’s ‘We close our eyes’.

I don’t so much remember my first computer as my first word processor. It was called ‘Multimate’ and they put ‘mate’ in the title just to try to defuse the inevitable falling out that would occur within fifteen minutes of the user getting acquainted. The Ctrl key was a big part of Multimate, as was the Shift key and the Alt key. If you wanted to, say, indent the paragraph, the user would have to press Ctrl, Shift and Alt all at the same time, punch in some IBM function keys with his forehead while trying to elbow the spacebar.

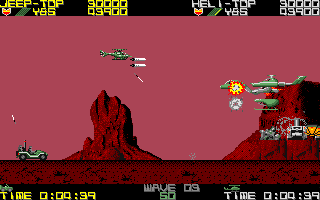

As I grow older, I plan to bore children by telling them about the Commodore 64. ‘You know that wasn’t 64 megabytes, it was 64 kilobytes. What we would have given for even 64 megabytes. And yet we still had fun. ‘Choplifter’, kids. Look it up online. You can still have fun with 64 kilobytes.’

Angela says…

Silkworm FTW.

Feel free to share your own responses to the topic, or to the authors’ responses, in the comments.

Posted in Author info

Tags: Andrew Humphreys, first computers, Matt Blackwood, MWF authors on, Tony Wilson

MWF 2010 authors on… Melbourne

Posted by Angela Meyer (LiteraryMinded)

If Sydney is the loud good looking kid in class who everyone gravitates towards but who you eventually discover has ADD and an eating disorder, Melbourne is the quieter, more measured kid who you don’t really like at the beginning of term but who is interested in the same things that you’re interested in, and whose parents own a really kickarse record collection.

A city that still strikes me, a lifelong Sydneysider, as unaccountably foreign and exotic. Every time I hear a tram bell I close my eyes and brace for impact.

I see myself living in Melbourne. Vividly. I do, no doubt, in a parallel universe. It took me too long to get there for the first time, but when I did the city was like certain people you have just met but seem to know already in some special, intuitive way. As if you’d dreamed them. I’d already discovered the landscapes of Clarice Beckett by then, so I had dreamed Melbourne.

Feel free to share your own responses to the topic, or to the authors’ responses, in the comments.

Posted in Author info

Tags: Andrew Humphreys, Kristel Thornell, Melbourne, MWF authors on, Tony Wilson

MWF 2010 authors on… mornings

Posted by Angela Meyer (LiteraryMinded)

I’ve given MWF guests a list of 15 random topics to respond to. The idea is to entertain and introduce you, the reader, to other sides of the MWF authors and their work, which may not be revealed on festival panels. The authors were allowed to respond in any way they liked, and were given no word limits. To learn more about the authors and what they’re doing at the festival, click their names through to their MWF bios.

I’m more a day-break person than I am a morning person. My wife is neither a day-break nor a morning person, and so I thought to invent a vibrating wristwatch that woke me and only me during my six years of breakfast radio. I thought to invent it, but unfortunately my complete lack of technical ability and the fact that it had already been invented stopped me making my millions.

I love dawns. For six years, it meant Triple R Breakfasters and time spent waking up with the rest of the city. Now it means sitting on a couch, sipping coffee and watching my ten month old strain through his morning nappy. We both watch The Gruffalo as he does this, and both love the owl.

Mornings start earlier and earlier now that I have children.

‘At this hour of the morning,’ he said, addressing nobody in particular, ‘people who are awake fall into two categories: the still and the already.’

So says a character in Italo Calvino’s story ‘The adventure of a wife’ to the protagonist, who has wandered into a cafe at six a.m. She, like the speaker, falls into the first category, since she is on her way home after being out all night.

In 1994, I was up at six a.m. almost every morning, but for the first part of the year I was a ‘still’ and in the second part I was an ‘already’. Initially I worked on the night shift as a security guard at a cardboard factory. (I think that’s what they made. I didn’t really care, so I never bothered to find out). After that, I worked as a postman, and I started work at 5.45. In both jobs I set a record of sorts: I had the longest hair of any security guard in Glasgow that year; and later I was the slowest postman in the entire city.

I became a connoisseur of tiredness during this period. The first critical distinction to be made on that subject is related to Calvino’s observation, since the tiredness of staying up too late is qualitatively different from the tiredness of getting up too early.

Mornings? Don’t do ’em.

I’m a morning person if you accept that morning is a state of mind, beginning when you decide it should. I think Descartes said something like you shouldn’t let anyone get you out of bed until you’re good and ready if you want to do decent mathematics. In a perfect world, it would be the same with writing, of course. But even on little sleep the morning can be golden for creative work, the brain surprisingly deft, somehow reborn.

Feel free to share your own responses to the topic, or to the authors’ responses, in the comments.

MWF 2010 authors on… Federico Fellini

Posted by Angela Meyer (LiteraryMinded)

I’ve given MWF guests a list of 15 random topics to respond to. The idea is to entertain and introduce you, the reader, to other sides of the MWF authors and their work, which may not be revealed on festival panels. The authors were allowed to respond in any way they liked, and were given no word limits. To learn more about the authors and what they’re doing at the festival, click their names through to their MWF bios.

Few directors give you such a hypnotic, rich sense of the inner life in all its density—its theatricality, lyricism, madness and libido.

He brought out the best in mythical actors. Mastroianni, of course. Giulietta Masina… I always think of her clownish soulful face in that gem, Nights of Cabiria. A movie that does what great art seems paradoxically capable of—being both hugely heartbreaking, bleak, and yet celebratory.

You wouldn’t know it from my name, but my mother is Italian and I consider myself as Italian as I am Australian. The fact that my grasp of the Italian language is very poor is irrelevant. And besides, you don’t need to understand Italian to watch Fellini. The images are everything.

Fellini was a bit af a stir amongst the foreign film directors blossoming in Melbourne during the 60s. The Italians were heavily represented, Visconti, Antonioni, Pasolini, and the younger Bertolucci to name just a few. Eight and a Half‘s dreamy subjectivity was a novel language to me, quite disorientating in a useful way. Juliet of the Spirits and Satyricon soon followed to raptuous reception. His star had faded a decade on, and it was the grittier realist film, La Strada and the late work, Armacord that have endured for me.

Feel free to share your own responses to the topic, or to the authors’ responses, in the comments.

Posted in Author info

Tags: Andrew Humphreys, Federico Fellini, film, Kristel Thornell, MWF authors on, Rod Moss

MWF 2010 authors on… time

Posted by Angela Meyer (LiteraryMinded)

I’ve given MWF guests a list of 15 random topics to respond to. The idea is to entertain and introduce you, the reader, to other sides of the MWF authors and their work, which may not be revealed on festival panels. The authors were allowed to respond in any way they liked, and were given no word limits. To learn more about the authors and what they’re doing at the festival, click their names through to their MWF bios.

Summer tends to do strange things to time, but in Finland the effect is breathtaking. Nights—in that old sense of those dark interludes during which you slept–are a brief, odd joke. At first, I especially found the birdsong around midnight disconcerting, like the sneaky onset of a subtle insanity. But the mind or the body adjusts. And then time seems to have become so generous, childhood-holiday elastic…

‘He flexes like a whore, falls wanking to the floor.’ (David Bowie.)

1/60 of a second, Piazza San Marco, Venice, 2003

The photograph above is part of a sequence at www.letusburnthegondolas.com. I took it in Piazza San Marco, in Venice. It reminds me of a portrait by Josef Sudek (reproduced below), in which, as Ian Jeffrey explains, ‘the man is accompanied by his shadow … and by his reflection …. [I]t is a portrayal of a subject reduced and simplified almost out of existence’. There’s a paradox at the heart of this quotation, because in Sudek’s photograph the man is reduced by multiplication. Not only that, but his doppelgangers – a broken black shadow and a will o’ the wisp white reflection – are unrecognisable reproductions. By contrast, the doppelgangers of folklore were indistinguishable from their originals: except for the fact that they cast no shadow and left no reflection.

Josef Sudek, Portrait of a Man, 1938

Josef Sudek, Portrait of a Man, 1938

The subject of my photograph is also a waiter (or rather, one of the two subjects is a waiter), but it is difficult to make sense of what is happening without recounting the precise circumstances under which the photograph was taken. So: I am sitting in front of a bar in an overpriced café. A waiter is standing behind the bar. Half of his bisected torso is visible at the extreme right edge of the frame. At frame centre there’s an espresso machine and a rack of upturned coffee cups. There’s a mirror above the cups, in which the reflection of the waiter’s back is visible. All of these elements are out-of-focus.

Behind me, over my right shoulder, is a plate-glass window which opens out onto the street. A reflection of a small part of this window, framed by drapes, is also visible in the mirror above the espresso machine. Because it’s dark outside, a faint image of the waiter’s face bounces back off the plate glass window into the café interior. That image is also visible in the mirror: the reflection of a reflection.

People walking past the café always look in. They can’t help it. It’s a reflex. So, I think, if I preset the focal point of my lens manually ‘inside’ the reflection in the mirror, I can capture someone looking through the glass from outside at the precise moment that their reflection passes the faint outline of the waiter, projected onto the glass from inside.

Because I am left-handed, I hold the viewfinder up to my left eye, and I have to pull it down and away in order to get enough space to flip the lever that advances the film. As I do so, I expel the air I have been holding in to keep the camera steady. So each exposure on a 35mm film represents a single breath and a discrete perception, both of which have a finite duration: in this case, 1/60s.

This particular image, which exists as a hypothesis in my head before I am able to test it experimentally, is doubly singular, because I know that I’ll only get one chance at it. The experiment can’t be repeated, because I’ll have to bring the camera up fast and shove it right in the waiter’s face, with no warning. I’m willing to do this once – I’ll take my chances and apologise afterwards – but I won’t get away with it twice.

The footsteps outside reach a particular pitch when someone is approximately two seconds away from the right location, before they actually appear in the mirror, so I’ll have to start moving the camera up to my eye when I hear that cue, before the image has presented itself to my eye.

Click.

1/60 of a second is – just, barely – long enough to distinguish the sound of the shutter opening from that of it closing, an interval during which I cannot in fact see anything, during which I am conscious of nothing: except duration itself.

What is the resulting photograph ‘about’? It includes three versions of the waiter. In one sense the bisected mannequin in the foreground at frame right is most real. It’s closest to the camera and is undeniably there, physically present. But that version of the waiter is an amorphous blob: half a white tuxedo, half a black tie, a quarter of a grey jawbone, an icon of the idea of the costume of a waiter, ‘reduced and simplified almost out of existence’. The man’s back, visible as a reflection in the mirror above the espresso machine, is further away, but clearer, more recognisable as an actual human being. Still, it’s turned away from us, expressionless by definition.

It’s only in the second-degree reflection bounced back from the plate glass that the man acquires a personality, but this minute, barely visible face floats uneasily next to that of an outsider peering in, whose naked, grainy curiosity is unbound by the blank protocols of service. Together, these two faces make up less than five per cent of the negative. They’re the only parts of the photograph in focus, but they never coincided or connected in reality.

But perhaps the most important thing about this photograph is what it doesn’t show. No-one ever asks the right question, the most puzzling question, the most important question: ‘How did you keep yourself out of the mirror?’

Feel free to share your own responses to the topic, or to the authors’ responses, in the comments.

Posted in Author info

Tags: Andrew Humphreys, capturing, David Bowie, Finland, Jonathan Walker, Kristel Thornell, MWF authors on, night, photography, time

MWF 2010 authors on… 1970s (pt 2)

Posted by Angela Meyer (LiteraryMinded)

I’ve given MWF guests a list of 15 random topics to respond to. The idea is to entertain and introduce you, the reader, to other sides of the MWF authors and their work, which may not be revealed on festival panels. The authors were allowed to respond in any way they liked, and were given no word limits. To learn more about the authors and what they’re doing at the festival, click their names through to their MWF bios.

This is a photo of my brother and I from a PixiFoto stand at the local shopping centre in 1972. Why? It’s one of my favourite photos, and the impulse towards nostalgia (especially as seen in family photos) is touched on in my book Martin Westley Takes a Walk.

People like to think of the 1970s as a time when something odd got into the water and people started to act very strangely indeed; uncharacteristic of either ‘traditional’ behaviour or more modern ways of life it was more like a parallel universe had opened up in the voluminous space of their loon pants and Oxford bags.

By 1974 almost every man, once chiselled, plain and smoothed down by tailored lines and brilliantine was now to be modelled on every ghastly variation of ‘the pop or rock musician’ (for no good reason at all) and had that all round dishevelled, lost, unwashed look. Every other woman was batty too: now hyper-motivated on self-improvement, they enrolled in wholesome crafts such as pottery, weaving or tie-dying or making strange works (neither art nor craft) with nails and string. Still smoking, still largely under-educated, and still drinking bad wine, they blundered on into a psychedelic-psychopathological alternative to good sense and judgement (of any kind). Or so it seems to some these days.

In the kitchen, long established routines of acceptable food preparation were ditched in favour of some of the wackiest creations ever known to our species. Just thumbing through my copy of Sonia Alison’s Love of Cooking (1975) I see compelling, mouth-watering recipes such as Danish Peasant Girl with Veil (an idiotic sort of apple crumble), Locksmith’s Apprentice (a laxative-action dessert job involving prunes), Syrup Tart (an unexotic and unappetising confection of sugar, fat and white flour), the thoroughly revolting Pilchard Pancakes au Gratin (featuring tinned pilchards in tomato sauce – a form of pure evil mixed with pureed weevil) and the killer, Spaghetti Egg Quickie (featuring tinned overcooked spaghetti in tomato sauce and poached eggs). I fancy we shall see none of this retro-fied at Poh’s corner.

So, the 1970s comes down to us as eccentric, weird, far-out, loony, slightly hysterical, scruffy, squiffy and squalid. But, there is a huge BUT coming.

BUT, this essentially experimental frame of mind with quite extreme shifts in the look and feel of society and culture will be recognised as an important tipping point in history, when a future orientated modernity that was so intolerant of tradition, other cultures, the past and even to a degree nature, was questioned and substantially replaced by an ethnic of tolerance, curiosity, experimentation and hybridity. The following comes from my new book City Life (London: Sage 2010):

‘Cities, especially large metropolitan cities, are the boldest expressions of any historical era and exemplify its values and character more than any other material manifestation. Rural landscapes across the world remain remarkably constant despite profound social changes, but cities are not only products of their age (even if they have only reshaped the foundations of previous eras), they seem to be the first to draw fire and criticism when things are perceived to be wrong. Equally, when a new age is dawning it is on the surface of cities that it begins to inscribe itself first. As the centre of political, cultural and administrative power the principal cities attract and retain an ancillary class of engineers, architects, designers and artists who are called upon to realise the material and aestheticised expressions of social and political elites, their values, forms of governance, commerce, often through show-case projects, often in prominent city spaces. However, the stirrings of new demands for change may not arise first among this professional class since their fortunes are so often tied to those in power or to rationalised dominant paradigms. As George Bernard Shaw remarked, “The reasonable man adapts himself to the conditions that surround him… All progress depends on the unreasonable man.” Therefore, it is often outsiders: students, the artistic avant-garde, new social movements (political, consumer, sexual, gender, race/ethnic etc.) and the so-called ‘hippies’ and ‘creative classes’ – together an important social strata of any major city – who painted in the first brushstrokes and began to live life in a new way and will new life-worlds and circumstances into being. Their combined efforts produced a tipping point for change in the 1970s across most Western nation states.

Portentously, in April 1970 the horse Gay Trip won the British Grand National. The 1970s were the beginnings of an epoch of revolutionary social and cultural transformation and from David Bowie’s gender-bending rock through the sexually liberating magazine Oz to Spare Rib and the Gay Times, everything, including received norms of sexuality and gender had been subjected to the most rigorous criticism and experimentation. The ‘70s created a culture, still alive today, that thrives on transformation and change as a permanent state and its role in the creation of new forms of city life cannot be underestimated. Later, in July 1970, enthusiasts brought Brunel’s revolutionary ship the SS Great Britain back for restoration in Bristol docks. It had to be for profoundly important reasons because it was brought back from the Falkland Islands at great expense. Such a move signalled that the new modern future was not going to be achieved by rejecting the past but by being inspired by it. Prior to the 1970s the modern impulse was future orientated and it worked as hard on destroying the past as it did on finding a future. As tourism scholars who specialised on the new heritage phenomenon found, one cannot destroy the past without creating a sense of loss and when that loss seemed to be the extensive industrial culture of Britain, it proved too difficult to bear. Personal and cultural biography, and memory itself was inscribed on the sorts of everyday objects and spaces that were retained and showcased by heritage collections. Critically, the impulse to preserve the SS Great Britain belonged to the gathering heritage sensibility that has been much mocked but it was an instance of a very important transformation. The search was no longer on for a singular aesthetic, a new look for a new perfectible age. Instead aesthetic beauty was being found in new places, in pre-industrial cultures, other cultures elsewhere, in the past(s), in textures and surfaces of old buildings, on the fringes and in newly discovered popular cultures from the past and present – in the nooks and crannies of all forms of city life, human and non-human. The crap men’s hair and the many crap towns that emerged then were not ends, were not intended outcomes but beginnings, the beginning of new becomings. Men’s hair would get better…

The 1970s reaction to the dominant culture of modern functionalism was to blow raspberries using whimsy and absurdity; adherence to the past provided a form of reversal and quirkiness that became the anti-motif. The Beatles did not eschew sentimentality but actively sought it in such things as brass band music. Everyone knew that brass bands were the epicentre of trad working class collective sentiments and they were not to be simply blown away or forgotten. Nobody was to be forgotten. Besides, it sounded interesting against the jangle of guitars. Or/and Indian instruments…

New communities of interest were coming forward to be defined and identified by objects, pasts and spaces on the verge of extinction but now to be recoded heritage or culture. This is how city life in places like Canterbury came to be changed and set on a new line of flight. There was a lot of recoding going on in city life now. Instead of finding the correct form, good taste transformed into eclectic taste, mixtures, hybrids and fusions. Instead of seeking the best way to live and identifying forms of life to reject and reform, a new kind of empathic curiosity took its place. If there was a degree of intolerance or rejection it was for modern utopias, futures that left the past and some groups behind. There was a new-found intolerance for the technocrat and scientists found to be working for corporations rather than for the common good and for progress.’

Today the 1970s can seem a mess, and the food a disaster but that is only because all the pieces of the world were thrown up in the air in order to be reconsidered afresh, with a more tolerant and open-minded attitude. How such a fragile, wobbly, improbable movement came to change the world is very life affirming for me. Maybe I should try Pilchard Pancakes au Gratin after all….

[i] George Bernard Shaw Revolutionist’s Handbook

On Saturday 4 September there will be a session called Living in the ’70s, featuring Francis Wheen and Frank Moorhouse. Get tickets here.

Posted in Author info

Tags: '70s, 1970s, Adrian Franklin, Andrew Humphreys, MWF authors on