Blog Archives

Thoughts on ‘Thoughts on Thoughts’

I always try to catch a few science sessions at MWF. I didn’t study science beyond Year 10 (somewhat regrettably) besides a bit of psych at Uni, so it’s a special, pleasurable challenge to wrap my head around the concepts and questions raised in sessions such as this afternoon’s Thoughts on Thoughts.

I always try to catch a few science sessions at MWF. I didn’t study science beyond Year 10 (somewhat regrettably) besides a bit of psych at Uni, so it’s a special, pleasurable challenge to wrap my head around the concepts and questions raised in sessions such as this afternoon’s Thoughts on Thoughts.

Chris Krishna-Pillay was our engaging and funny host, chatting to cognitive neuroscientist and raconteur Michael Corballis. It was a free session in the Yarra Room and the audience was crowded in, standing and sitting on the floor all the way up to the back. Corballis explained that he came to write ‘popular science’ because in his many years of lecturing he often encountered students who, simply, didn’t understand many of the concepts in the (academic) language they encountered. With the pop science, you have to ‘let loose a little bit’, he said. His latest book Pieces of Mind: 21 Short Walks Around the Human Brain features short, sharp chapters that began as magazine articles.

Corballis spoke a lot about language, about what we don’t know (and about what he’s trying to find out) as much as what we do. He believes that language capacities in human beings have evolved incrementally (not with a ‘big bang’, as Noam Chomsky has suggested). He supports the theory that language is related to, and has evolved from, gestures as opposed to sounds and calls, eg. an intentional gesture of an ape grooming another, as opposed to their more emotive and involuntary calls. The gesture theory is supported by the fact that sign language, in MRI scans, lights up the same area of the brain, in the hippocampus, as does speech language. Corballis’ research takes him many places—from the now sequenced Neanderthal genome, to fossil evidence, to studying chimps and bonobos.

Other animals do communicate, but language is separate from the communication of simple concepts. For example, we can’t know, and it’s improbable, that a dolphin or a dog or other intelligent mammal can express ideas of what happened yesterday, or what is going to happen tomorrow. This is part of what makes a language, the discussion of what’s happening, what has happened and what will.

Memory is therefore intertwined with language: ‘the ability to communicate about the non-present’, as Corballis put it, the ‘means of describing things that are not in front of you’. Humans have what he called ‘episodic memory’. Whether animals actually remember an ‘episode’, or whether they are simply ‘conditioned’ to act a certain way is not something that can currently be proved. For example, if a dog buries a bone, and he goes to retrieve it, is he specifically recalling the ‘episode’ of burying it, or is it more instinct, sense, and smell that come in? It is an absolutely fascinating question. And I like that sessions like this place those kinds of (possibly unanswerable) questions in your mind.

To go a step further, Corballis discussed the fact that human beings are capable of having ‘thoughts about thoughts’, and about other people’s thoughts, but we cannot know if other intelligent species have this level of awareness. It is probable that we are unique in this aspect, and that it is tied in with our capacities for language and episodic memory.

We are limited with what we can know about memory, too, because animals and young children (before language) cannot tell us what they remember. Language is inadequate, in many respects, Corballis explained, because there’s more to memory than we’re able to get from language, such as the specificities of sense memory (though of course some of the greatest writers do try, and manage to spark our recognition).

At one point, a question was raised about dreaming. We still do not know the exact purpose of (human) dreaming, though there are many theories. Corballis said that animal dreaming is pretty much to do with the consolidation of memory (ie. a rat coding the maze). He says that human dreams are undeniably strange! Our own dreaming and mental time travels ‘help us frame futures and even our sense of self’, he said, but there will always be a ‘random component’. Dreams can be like Rorschach tests, Corballis said, we can read into them what we will.

—

Michael Corballis will also be appearing on The Story of Science panel, tomorrow (Saturday 1 September) with Margaret Wertheim, Peter Doherty, Elizabeth Finkel and Leah Kaminsky. His most recent books are Pieces of Mind: 21 Short Walks Around the Human Brain and The Recursive Mind: The Origins of Human Language, Thought, and Civilisation.

See some of my previous vaguely sciencey MWF posts:

Lab coats, lit journals & marrying frogs (2011)

Birds of a feather (2011)

Complex life (and our plastic brains), a beautiful fluke (2010)

A work in progress on Work in Progress

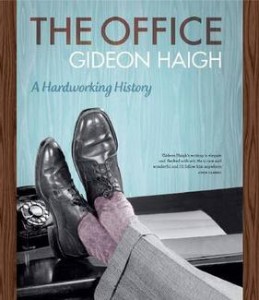

Geoffrey Blainey in crumpled suit and Gideon Haigh in torn jeans, 59 books between them—

Geoffrey Blainey in crumpled suit and Gideon Haigh in torn jeans, 59 books between them—

On the elevators and steel skeleton constructions

coinciding with the growth of a city.

White collars.

Fogged windows and chocolate biscuits: a comfortable routine.

Both Chicago and Melbourne had height limits, for a time, on office buildings. ‘Some of the earlier skyscrapers [in Chicago] sat like a petrified forest’, said Haigh, until the ’20s and ’30s when more skyscrapers were built.

In Melbourne, the six story limit related to the length of fire ladders. ‘People wouldn’t go into the lifts’, said Blainey. They were afraid.

The Manchester Unity building on Swanston Street is the ‘little brother’ (as Haigh put it) of the Chicago Tribune building, which was built from Raymond Hood’s competition-winning design for the most beautiful office building in the world. (Aside: glorious art deco.)

You used to be able to tell, said Blainey, what line of work people were in, by the way they dressed. Office workers were clean. Positions in some professions were determined by uniform, now we have titles. And many titles don’t tell us anything.

How do we judge the output of office workers?

‘We come up with means to judge an office worker’s productivity.

9-5 or 8-6

there’s an expectation of

minimal diligence by presence,’

said Haigh.

It’s hard to judge productivity, in an office, any other way.

In the early mixed-gender office men were worried they’d be distracted by ‘female frivolity’, or perhaps the women would become coarse. They were still segregated: telephone operators, secretaries; in the basement. Typing was ‘feminine’ but relied upon. Lorena Weeks fought for the shiftman’s job and, eventually, she won.

Blainey remembered a boy writing his school essays on a typewriter. At the time, they didn’t know what to think of him.

Haigh was ahead of the technology in the early ’90s, taking a giant computer home from the office each night to do his writing.

Now we can easily work from our homes/on the move. ‘Perpetual contactibility,’ Haigh called it.

The office is inescapable (she types, working from home).

At least as long as the physical office exists, we can leave it behind—Haigh (paraphrased).

One can be seduced by corporate culture. One can belong.

Or there are those subtle acts of subversion: stealing stationery, satirical emails.

But, as an audience member pointed out, we’re not so assured of ‘careers’ now. Contract work, downsizing, takeovers, discrepancies between the salaries at the lowest and highest levels. Decisions are made a long way from where they’re implemented (but maybe, the panel says, that’s not new).

But work itself. Blainey and Haigh embody it, because they enjoy what they do:

‘It gives me enormous pleasure,’ said Blainey, who remembers the joy of working with the fruiterer as a boy.

For Haigh there is the satisfaction of self-sufficiency, there’s a desire to improve and to be productive. Blainey is an inspiration to him.

Gideon Haigh’s latest book is The Office: A Hardworking History and Geoffrey Blainey’s latest book is A Short History of Christianity.

The Age Book of the Year Awards

The Age Book of the Year awards were announced last night at the Melbourne Writers Festival 2012 opening event, prior to Simon Callow’s enthusiastic, informative Keynote speech on Charles Dickens.

The Age Book of the Year awards were announced last night at the Melbourne Writers Festival 2012 opening event, prior to Simon Callow’s enthusiastic, informative Keynote speech on Charles Dickens.

The awards, now in their 38th year and highly regarded, were presented by Age literary editor Jason Steger. They went to…

Fiction

Foal’s Bread by Gillian Mears (Allen & Unwin)

Poetry

The Brokenness Sonnets I-III and Other Poems by Mal McKimmie (Five Islands Press)

Nonfiction

1835: The Founding of Melbourne and the Conquest of Australia by James Boyce (Black Inc.)

Overall winner / Age Book of the Year

1835: The Founding of Melbourne and the Conquest of Australia by James Boyce (Black Inc.)

Boyce was very humble about his win, he commended the Age for continuing to support literature and authors, and he very gratefully acknowledged author and historian Inga Clendinnen, who has been a supporter of his work.

This afternoon the winning authors will be reading from their work in The Age Book of the Year Reading. It’s a free event at 2:30pm at BMW Edge. Do come along.

—

Just in case I/we don’t get a chance to write about Simon Callow’s Keynote, his Lateline interview with Tony Jones is online, and of course, you can check out his writing. I can personally recommend (though not on the subject of Dickens) his essay in the latest Sight and Sound (UK) magazine on Orson Welles (another figure he’s passionate about, he’s currently working on the third volume of his biography). See also my Q&A with Callow on writing and playing Dickens.