Blog Archives

Switching to Fiction: Christopher Kremmer, Anna Funder, Leslie Cannold and Malcolm Knox

When Christopher Kremmer fled from an op shop where he’d found a bound collection of old Sydney Morning Herald newspapers from the period when his father had been a jockey in the Melbourne Cup, he realised that his ‘whole life was about running away from the past’. This time, he decided to turn back around and face it, and was drawn into the stories of the horseracing world. His novel The Chase tells the story of a scientist, Jean Campbell, trying to root out drug use in the horse racing industry. Even for the experienced non-fiction writer and journalist, research was nigh impossible: ‘the world of horseracing is a world of secrets … it’s all about masking what goes on to increase the odds’. To make his task even more complicated, the real-life scientist Kremmer was basing Campbell on had never left any records.

When Christopher Kremmer fled from an op shop where he’d found a bound collection of old Sydney Morning Herald newspapers from the period when his father had been a jockey in the Melbourne Cup, he realised that his ‘whole life was about running away from the past’. This time, he decided to turn back around and face it, and was drawn into the stories of the horseracing world. His novel The Chase tells the story of a scientist, Jean Campbell, trying to root out drug use in the horse racing industry. Even for the experienced non-fiction writer and journalist, research was nigh impossible: ‘the world of horseracing is a world of secrets … it’s all about masking what goes on to increase the odds’. To make his task even more complicated, the real-life scientist Kremmer was basing Campbell on had never left any records.

Then there’s the balancing act between a non-fiction writer’s research instinct and the novelist’s creative impulse: ‘You overresearch it, but you get to a point where you need to let go of those real people. Once you start doing that you start to be able to pour yourself into these character.’

Chair Geordie Williamson asked whether there was any pressure on Anna Funder to follow up her acclaimed account of the former East Germany, Stasiland, with something in a similar vein? ‘My husband said I had second-album syndrome, which I don’t think is true,’ said Funder of her new novel, All That I Am.

In non-fiction, Funder believes, it’s important to honour the people you’re writing about, so in Stasiland, for which she spoke with people whose courage had been ‘almost unbelievable’, she wanted to pay tribute to that. With All That I Am, though, the people on which Funder based her characters are no longer alive, and what happened isn’t known, so ‘I looked at shards of history and put together a plot which I think is the most likely thing that happened’. While this lack of material might seem less advantageous, there is an upside: ‘The biggest moral limit of non-fiction is not being able to represent the consciousness of your characters from the inside. That was a huge liberation.’

with people whose courage had been ‘almost unbelievable’, she wanted to pay tribute to that. With All That I Am, though, the people on which Funder based her characters are no longer alive, and what happened isn’t known, so ‘I looked at shards of history and put together a plot which I think is the most likely thing that happened’. While this lack of material might seem less advantageous, there is an upside: ‘The biggest moral limit of non-fiction is not being able to represent the consciousness of your characters from the inside. That was a huge liberation.’

Leslie Cannold ‘didn’t make a conscious choice to write a novel’. The impetus for writing The Book of Rachael was a BBC documentary attempting to unearth historical truths about the life of Jesus. Cannold ‘started wondering what my family were up to’ at this time – but it became clear that the historical record was not concerned with women. Fronting up to the library, Cannold demanded everything that existed on Jesus’s sisters, but she was told there was basically no existing material on the subject. Cannold decided it would be her responsibility to tell such a story.

Where fiction and non-fiction do mix, suggested Malcolm Knox, was ghostwriting. Someone like the famously laconic Bart Cummings is hard to write a 300-page book about, so the tools of fiction can assist in creating a narrative. Yet there is a point at which you have to stop and go no further – you can’t make anything up. In regard to Knox’s novel The Life, there was at least one good reason not to write a biography of surfer Michael Peterson – one had already been written. But he ‘was always about 50 per cent fiction anyway’, said Knox.

All the guests thought of fiction as serving a different purpose to non-fiction in telling a story. Cannold thought that if she wanted to write about something about which there was very little known, she would elect to use fiction. Kremmer thought that, for his next book, he would probably be returning to the more familiar ground of non-fiction, but not because fiction was unsatisfying: ‘I found it one of the great experiences of my writing career’.

MWF podcast interview: Steve Hely

Do you know what it takes to become a famous novelist? Apparently, you only need a bunch of rules (including ‘Rule 9: At dull points include descriptions of delicious meals’), a desire to show your ex-girlfriend up at her wedding, and a guest appearance on Law and Order: SVU. Steve Hely’s How I Became a Famous Novelist has been described as ‘an expose of the world of books and writing’ and as ‘bulging with humour, fat with arch parody, obese with deft satire, each page deserving of a dog ear of commemoration’.

MWF blogger Estelle Tang spoke to Steve about comedy, the pain of writing, and how to tell a dud book from a good one.

Listen or Download audio here

The acrobatic intelligence of César Aira

Many well-read locals have unwittingly converged in their recent reading recommendations. The cynosure of their praise, César Aira, is a prolific author whose oeuvre is so extensive and popular at home in Argentina that Michael Greenberg, writing in the New York Review of Books, described it as having ‘engendered a mini-industry in Buenos Aires, involving start-up presses as well as more established publishers that share the job of putting Aira’s work between covers’. There are so many books that no one seems to be able to count them all (counts range from fifty to over eighty). As far as I can tell, though, only five of Aira’s books have been translated into English: Ghosts, The Literary Conference, The Seamstress and the Wind, How I Became a Nun and An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter.

Now, when the piper pipes, I follow. So now I have three of these slim volumes in my possession. I read Ghosts before I knew how Aira writes, that he slings his pen around after his thoughts without revising his work, making for an unbelievably unsettling and exhilarating reading experience. If television crime procedurals are at one end of the plot structure spectrum, with their revelations doled out in compact and predictable doses, Aira is continually repositioning the other end of the spectrum with his busy and elastic novels.

Ghosts opens on New Year’s Eve, amid a hot summer’s day of work. Slaving and joking, a group of construction workers are finishing up in order to celebrate freely that night. The night watchman, Raúl Viñas, lives on the top floor of the incomplete building with his family; his children play around the empty swimming pool and gaze out the unfinished walls. The eldest child, Patri, is quiet and dutiful, but entranced by the ghosts who roam the site. Sidestepping the breathlessness often associated with the magic realism of South America, Aira turns his attention to these spectres with the same curiosity and creative logic he applies to everything.

To describe the characters and the events of the novel is not to give a sense of why Aira’s work is so fascinating. Reading Aira is much like hearing a tale as a child, before the idea of story is familiar, both its wonders and its clichés. The formidable power a writer holds becomes salient in Aira’s literary wanderings: we’re held hostage to what Scott Bryan Wilson called Aira’s shifts of attention. Whether it’s the unwittingly comical length of a youth’s hair or a digression on architecture and its relationship to dreams, in Ghosts we reawaken to the radical nature of putting words to paper, and are grateful for the acrobatic intelligence of the scribe committing them there.

See Aira in conversation with his English-language translator, Australian Chris Andrews: in English, 4pm on 27 August; or in Spanish, 2:30pm 28 August.

Or celebrate 75 Years of New Directions, famed publisher of experimentalists Dylan Thomas, Ezra Pound and Cesar Aira. This event is free, but booking is required.

Melbourne Writers Festival program launches tomorrow

Yes, that’s right: the Melbourne Writers Festival program will be available in your copy of the Age tomorrow morning, or online at our website. You’ll be able to stop making your dream author wishlist and start compiling a real one.

The MWF team have been working tirelessly for months to put together a sublime 2011 program. Running for 11 days, the program boasts over 300 sessions and 400 guests, including some of the most exciting, most respected and most beloved writers the world has to offer.

If you feel like even a day is too long to wait, you can already check out our Schools Program online. Tickets for the 2011 Schools Program are already available; book in to see literary superstars ranging from acclaimed fiction writer Maile Meloy to local heroes Peter Goldsworthy and Steven Amsterdam taking residence in Federation Square haunts, ACMI cinemas, ArtPlay, the Wheeler Centre and the Immigration Museum.

We’re unbelievably excited – less than a month to go until our first events. You can expect some fabulous opportunities to eat with your favourite authors, discover literary Melbourne, and discuss the future of reading and writing. Whether you love fiction, journalism, poetry, graphic novels, crime, music … and more, or all the above, we think we’ve got you covered. And stay tuned for our Keynote Events: trust me, you’ll want to be there.

Reading Melbourne

I’ve been home now for a few days. After spending some weeks prodigally gadding about with other cities, I’ve needed some help against my post-holiday blues. Don’t get me wrong: I’ve always lived in Melbourne, and it has my love for now and ever. But its welcoming embrace has been winter-chilly, its kissing cheek cold, and I have needed a bit of encouragement to fall back in love with it.

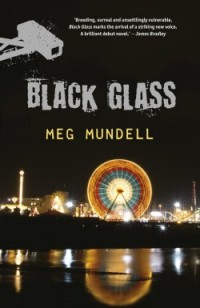

Luckily, Melbourne has no shortage of storytellers to assist with this reunion. In particular, there have recently been a few future-Melbourne books, extrapolating on existing geography and concerns to imagine a city strange and yet familiar. I recently had the pleasure of interviewing Meg Mundell, who was born in New Zealand but has lived in Melbourne for over a decade. Meg is the author of Black Glass, which envisions a near-future Melbourne (although AFL is still in evidence as the favourite sport, characters remember Cate Blanchett as an actress of yore).

Luckily, Melbourne has no shortage of storytellers to assist with this reunion. In particular, there have recently been a few future-Melbourne books, extrapolating on existing geography and concerns to imagine a city strange and yet familiar. I recently had the pleasure of interviewing Meg Mundell, who was born in New Zealand but has lived in Melbourne for over a decade. Meg is the author of Black Glass, which envisions a near-future Melbourne (although AFL is still in evidence as the favourite sport, characters remember Cate Blanchett as an actress of yore).

I read Black Glass a few months ago, but it popped up in my head again and again on my travels. A common topic in travellers’ conversations is politics; I did some patient explaining about the 2010 leadership spill to New Yorkers in dive bars, and I saw the church in Iceland that Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi disliked enough to suggest it should be bulldozed. Among all this talk of politicians, I couldn’t help but recall the government that Meg predicts for us in her novel. People who don’t have identity documentation, including children like Black Glass protagonists Tally and Grace, are unable to work legally, so they are forced into dangerous work on society’s fringes.

Not only is the government inhumanely blind to these people, but it also operates much like a corporation with a lot to lose. One character, Luella, a government official, trades newsworthy tidbits for control over how new policies will be represented by her reporter allies. When I asked Meg what Luella’s government wanted, she said: ‘To be re-elected’. This comment brought to mind not something from our possible future, but something fixed in our history: last year’s national election, in which Labor’s pre-election performance was criticised for its hollow tactics. But it’s not all doom and gloom in Black Glass. Lost as they are, Tally and Grace meet some people who help them along the way.

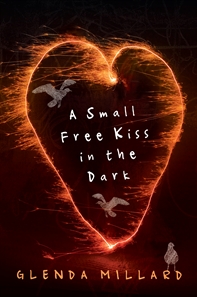

And it’s this idea of support and friendship for marginalised — indeed, homeless — people that first sparked the idea for Glenda  Millard’s A Small Free Kiss in the Dark, a young adult book that has been shortlisted for and won many awards. Young Skip runs away from school only to find himself in a city suddenly besieged by war. He befriends a homeless man named Billy, and an even younger boy called Max. Together they help each other to survive the onset of planes, soldiers and isolation.

Millard’s A Small Free Kiss in the Dark, a young adult book that has been shortlisted for and won many awards. Young Skip runs away from school only to find himself in a city suddenly besieged by war. He befriends a homeless man named Billy, and an even younger boy called Max. Together they help each other to survive the onset of planes, soldiers and isolation.

Though A Small Free Kiss in the Dark is set in a city that is never named, it contains hints that a Melburnian would easily take. I was moved by the little band’s pursuit of refuge through underground train passages, in a state library and in a fun fair that I had no trouble imagining as an abandoned Luna Park.

In non-fiction Melbourne reads, I’m looking forward to Sophie Cunningham’s Melbourne, due out in August.

What are your favourite Melbourne books?