Blog Archives

A work in progress on Work in Progress

Geoffrey Blainey in crumpled suit and Gideon Haigh in torn jeans, 59 books between them—

Geoffrey Blainey in crumpled suit and Gideon Haigh in torn jeans, 59 books between them—

On the elevators and steel skeleton constructions

coinciding with the growth of a city.

White collars.

Fogged windows and chocolate biscuits: a comfortable routine.

Both Chicago and Melbourne had height limits, for a time, on office buildings. ‘Some of the earlier skyscrapers [in Chicago] sat like a petrified forest’, said Haigh, until the ’20s and ’30s when more skyscrapers were built.

In Melbourne, the six story limit related to the length of fire ladders. ‘People wouldn’t go into the lifts’, said Blainey. They were afraid.

The Manchester Unity building on Swanston Street is the ‘little brother’ (as Haigh put it) of the Chicago Tribune building, which was built from Raymond Hood’s competition-winning design for the most beautiful office building in the world. (Aside: glorious art deco.)

You used to be able to tell, said Blainey, what line of work people were in, by the way they dressed. Office workers were clean. Positions in some professions were determined by uniform, now we have titles. And many titles don’t tell us anything.

How do we judge the output of office workers?

‘We come up with means to judge an office worker’s productivity.

9-5 or 8-6

there’s an expectation of

minimal diligence by presence,’

said Haigh.

It’s hard to judge productivity, in an office, any other way.

In the early mixed-gender office men were worried they’d be distracted by ‘female frivolity’, or perhaps the women would become coarse. They were still segregated: telephone operators, secretaries; in the basement. Typing was ‘feminine’ but relied upon. Lorena Weeks fought for the shiftman’s job and, eventually, she won.

Blainey remembered a boy writing his school essays on a typewriter. At the time, they didn’t know what to think of him.

Haigh was ahead of the technology in the early ’90s, taking a giant computer home from the office each night to do his writing.

Now we can easily work from our homes/on the move. ‘Perpetual contactibility,’ Haigh called it.

The office is inescapable (she types, working from home).

At least as long as the physical office exists, we can leave it behind—Haigh (paraphrased).

One can be seduced by corporate culture. One can belong.

Or there are those subtle acts of subversion: stealing stationery, satirical emails.

But, as an audience member pointed out, we’re not so assured of ‘careers’ now. Contract work, downsizing, takeovers, discrepancies between the salaries at the lowest and highest levels. Decisions are made a long way from where they’re implemented (but maybe, the panel says, that’s not new).

But work itself. Blainey and Haigh embody it, because they enjoy what they do:

‘It gives me enormous pleasure,’ said Blainey, who remembers the joy of working with the fruiterer as a boy.

For Haigh there is the satisfaction of self-sufficiency, there’s a desire to improve and to be productive. Blainey is an inspiration to him.

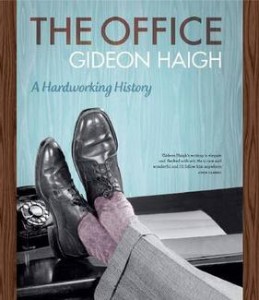

Gideon Haigh’s latest book is The Office: A Hardworking History and Geoffrey Blainey’s latest book is A Short History of Christianity.