Blog Archives

The Age Book of the Year Awards

The Age Book of the Year awards were announced last night at the Melbourne Writers Festival 2012 opening event, prior to Simon Callow’s enthusiastic, informative Keynote speech on Charles Dickens.

The Age Book of the Year awards were announced last night at the Melbourne Writers Festival 2012 opening event, prior to Simon Callow’s enthusiastic, informative Keynote speech on Charles Dickens.

The awards, now in their 38th year and highly regarded, were presented by Age literary editor Jason Steger. They went to…

Fiction

Foal’s Bread by Gillian Mears (Allen & Unwin)

Poetry

The Brokenness Sonnets I-III and Other Poems by Mal McKimmie (Five Islands Press)

Nonfiction

1835: The Founding of Melbourne and the Conquest of Australia by James Boyce (Black Inc.)

Overall winner / Age Book of the Year

1835: The Founding of Melbourne and the Conquest of Australia by James Boyce (Black Inc.)

Boyce was very humble about his win, he commended the Age for continuing to support literature and authors, and he very gratefully acknowledged author and historian Inga Clendinnen, who has been a supporter of his work.

This afternoon the winning authors will be reading from their work in The Age Book of the Year Reading. It’s a free event at 2:30pm at BMW Edge. Do come along.

—

Just in case I/we don’t get a chance to write about Simon Callow’s Keynote, his Lateline interview with Tony Jones is online, and of course, you can check out his writing. I can personally recommend (though not on the subject of Dickens) his essay in the latest Sight and Sound (UK) magazine on Orson Welles (another figure he’s passionate about, he’s currently working on the third volume of his biography). See also my Q&A with Callow on writing and playing Dickens.

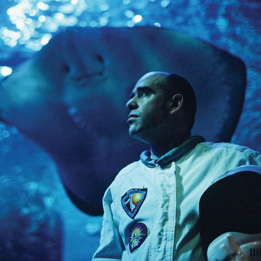

Book review: Beneath the Darkening Sky by Majok Tulba

Hamish Hamilton (Penguin)

Hamish Hamilton (Penguin)

9781926428420

July 2012

It’s taken me a little while to get over Majok Tulba’s unflinching novel about a young boy kidnapped by rebels and forced to become a soldier. On the cusp of adolescence Obinna is forced to witness unimaginable horrors, from murder to rape, starvation, and children being blown up by landmines.

Obinna, whose (first) nickname is Baboon, dares to continue dreaming, remembering, and questioning. But the rebels continue to break him, to beat him down. My heart ached. Sometimes I had to put the book down, to walk away.

But Majok Tulba manages to extract some beauty from this horror. How does he do it? Maybe it’s because the love of his own South Sudanese village is so strong. Tulba imagines, in this novel, what would have happened had he been tall enough to have been recruited. Tulba came to Australia when he was 16, and it’ll be amazing to hear him speak about Beneath the Darkening Sky at the festival, about the choices he made in the novel: what to show, who to focus on.

The dream sequences often centre around Obinna’s lost village and the people in it (many also gone). For the reader, the dreams are welcome relief from the horror, but they are not entirely full of hope—they are sweet but often twisted. In an early dream sequence, the villagers, including Obinna’s mother and father, sing and clap around the bonfire. No one dances except his friend Pina:

Pina jumps and spins, turning her body sideways as she flies. Her dance is frantic. Pina moves faster than I thought anyone could.

Even though everyone is smiling, a bad feeling cramps up my stomach. Like I’m watching a car engine rattling, until it explodes. My village, singing for Pina’s crazy dance, looks like it’s shaking, about to erupt. Everything is about to fall apart.

Tulba’s prose is striking. Obinna’s voice is strong—he deals with much of the horror, at least for a time, through the heartbreakingly innocent eyes of a child. When he first sees a woman beaten, for example, he thinks: ‘Maybe she’s sleeping.’ The first time he witnesses a boy being killed by a landmine, which happens almost in slow motion for the reader, he notes: ‘Landmines don’t kill you, they eat you.’ There are some incredibly memorable lines.

Looking at my notes now I realise, in my memory, I have transposed the dream before the ending for the actual ending. There’s just so much you don’t want to happen, but it does. It must, for this story to be so powerful. While reading the book, I thought it would give me nightmares, but instead I dreamt of children dancing. Like Obinna, I dreamt of something that was a life buoy, keeping hope afloat.

This book is devastating, but it isn’t relentless. And it is important. One reason it is important (among many) is that it reminds you that the person sitting next to you on the tram, standing by you on the street, sitting at the bar—whether a refugee or not—could have endured horrors you couldn’t even fathom. It’s a reminder of the importance of kindness, of generosity, of listening, in a world that can be both spectacularly beautiful and overwhelmingly cruel.

—

Majok Tulba will be discussing The Other Africa with Kwame Anthony Appiah, Uzodinma Iweala, Sefi Atta, and Arnold Zable on Friday 24 August at 2:30 pm, and will be reading from his work in The Morning Read session on Saturday 25 August at 10:00 am.