Blog Archives

MWF 2010 authors on… their first computer

Posted by Angela Meyer (LiteraryMinded)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macintosh_Classic

She was a first gen Mac, I was but a starry-eyed Year Eight student.

We got to touch for thirty minutes a week. Mostly awkward fumbles with a square mouse playing Minesweeper while humming Go West’s ‘We close our eyes’.

I don’t so much remember my first computer as my first word processor. It was called ‘Multimate’ and they put ‘mate’ in the title just to try to defuse the inevitable falling out that would occur within fifteen minutes of the user getting acquainted. The Ctrl key was a big part of Multimate, as was the Shift key and the Alt key. If you wanted to, say, indent the paragraph, the user would have to press Ctrl, Shift and Alt all at the same time, punch in some IBM function keys with his forehead while trying to elbow the spacebar.

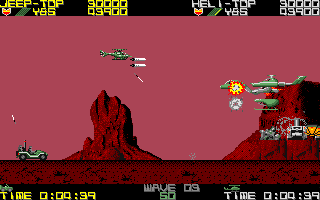

As I grow older, I plan to bore children by telling them about the Commodore 64. ‘You know that wasn’t 64 megabytes, it was 64 kilobytes. What we would have given for even 64 megabytes. And yet we still had fun. ‘Choplifter’, kids. Look it up online. You can still have fun with 64 kilobytes.’

Angela says…

Silkworm FTW.

Feel free to share your own responses to the topic, or to the authors’ responses, in the comments.

Posted in Author info

Tags: Andrew Humphreys, first computers, Matt Blackwood, MWF authors on, Tony Wilson

MWF 2010 authors on… which dead author they’d have for dinner and why

Posted by Angela Meyer (LiteraryMinded)

I’ve given MWF guests a list of 15 random topics to respond to. The idea is to entertain and introduce you, the reader, to other sides of the MWF authors and their work, which may not be revealed on festival panels. The authors were allowed to respond in any way they liked, and were given no word limits. To learn more about the authors and what they’re doing at the festival, click their names through to their MWF bios.

Kurt Vonnegut, not sure how he would taste, but if he’s anything like his writing, he would be lean, gluten free, and leave a lasting impression.

I thought it would be easy to think of someone, but actually, I have met a fair few renowned authors that have not lived up to expectation. The gap between authorial persona and the real person can be enormous. I suspect that as a rule it’s better to read the books and keep a wide berth of brilliant authors dead or alive. However, I have also been honoured to meet writing legends Isabel Allende and Marie Darrieussecq. If I could bring back to life the Botswanan writer Bessie Head and dine with her, I’d tell her that her novella Maru is a sublime poetic achievement. I doubt she’d snap at me for the compliment. I think she’d smile graciously. And then I’d thank her for leaving such a jewel for others to read behind.

Henry James. I just want to know what his voice sounded like.

It would have to be Michel Foucault. There are many questions I would like to ask him: did you really change your position to the extent that there is no point in reading your earlier writings? How does the concept of ‘apparatus’ relate to ‘discursive practices’ and to ‘assemblage’? and many others. However, there would not be much point as he would probably continue to answer them in his provocatively enigmatic way. So perhaps we could just have a quiet tête-a- tête.

Angela says…

Albert Camus, to talk about then and now in a ‘burning and frigid, transparent and limited universe in which nothing is possible but everything is given, and beyond which all is collapse and nothingness’.

Feel free to share your own responses to the topic, or to the authors’ responses, in the comments.

MWF 2010 authors on… the 1970s (pt 1)

Posted by Angela Meyer (LiteraryMinded)

I’ve given MWF guests a list of 15 random topics to respond to. The idea is to entertain and introduce you, the reader, to other sides of the MWF authors and their work, which may not be revealed on festival panels. The authors were allowed to respond in any way they liked, and were given no word limits. To learn more about the authors and what they’re doing at the festival, click their names through to their MWF bios.

Is summed up in a black, long-sleeved, boat-necklined wool dress my mother bought in 1974. She still has it. It is the glory of vintage apparel defined.

When I should have been in my twenties, black and in New York instead of being four, in Warrandyte and dubbed Grandmaster Flashdrive.

The 1970s started for me with the Springbok tour of Australia. I didn’t know anything about politics – or South African politics – at the time, but I remember the chant ‘Paint them black and send them back’, and remember thinking it was racist and wondering what it was for. I also remember seeing television images of police riding their horses into demonstrators, and 19-year-olds (they seemed all grown up to me then) with bloodied faces.

We talked about it a bit in my house: my mother protested against the Springbok tour, against the Vietnam War. She took a cushion along to sit down on Bourke Street, and I remember watching that mass of humanity sitting on Bourke Street on television and hearing the wildly differing estimates of people numbers. Why did the police always say there were fewer than what the demonstrators said?

We lived in Seymour and in the 1970s I went with my brother to the swimming pool and we ate sunny boys and razzes and I first discovered girls, notably by pushing them into the pool to show you liked them. One of their big brothers beat me up on the way home once and put a stop to that.

There were elm trees lining Station Street in those days and the cicadas used to sing in them when it was hot. There were other streets in town called Railway Street, and Loco Street, which was Seymour’s Struggletown.

The Vietnam War sizzled its way into my memory because we saw it every night with our chops and mashed potatoes and steamed carrots. Our tv was on top of the fridge and it chirruped on while we ate. I remember announcements of ‘three diggers were killed and two were wounded’, or something like that, and Peter Couchman standing in villages in Vietnam with a chopper in the background messing up his hair, talking about places called Nui Dat and Vung Tau and Bien Hoa.

I also seem to remember an expression you heard on the news at that time: ‘he was dead before he hit the ground’. I don’t know if that’s my memory playing tricks on me, but I swear newsreaders used to say that. Then how did they know?

And the politicians coming on tv saying if we didn’t stop the downward thrust of Communism they’d be here those Reds, under our beds, probably ravishing our wives and mothers by the tankstands, just as the Huns were going to in WWI or the Japs were in WWII.

Of course there is the searing image of a little girl running down the street naked with her back on fire, and the Americans afterwards saying it was a mistake.

This was a televised war, so we saw it all: the Saigon police chief shooting a man through the head and him collapsing in the street, the NVA approaching Saigon in their tanks and the young, rich and wealthy Vietnamese kids sitting in cafes playing dice games.

Uh oh.

Something dawned on me with that televised image. My brother had been called up to the war, but the change of government in 1972 let him off the hook. By the mid-seventies I was understanding this was more than just a war in a far off country among people about whom we knew very little. This was about justice at home as well. Our government was conscripting young men and sending them away to kill and be killed. This was what the demonstrations were about. As well as about the mayhem we were producing overseas.

Yet here were some young Vietnamese kids sitting around playing dice while the Commies advanced on Saigon! (Maybe we’d been sold a crock?)

My mother said she would protect any draft dodger who went underground, and I didn’t get what going underground was, and why you would do it, although it did sound vaguely like fun. I imagined riding my skateboard through tunnels. I also heard about young male politicians who were encouraging young men to go to the war, and the question was continually raised in my house: why didn’t they go themselves?

In between learning about the world I was learning about girls and asking them to the local Show or the movies, vaguely trying to put my arm around them and realising they were really, well, different.

We wore high heeled shoes and flares and messed around with strange ways of doing our hair, growing it lank and slicking it back. We did kung fu and went to Bruce Lee movies. The guys I went to school with listened to Nutbush City Limits and the Electric Light Orchestra and Queen, bands I detested.

Now my little boys play We are the Champions on their iPods, and I suppose it goes around.

Just like the wars. As I write this, last week Julia Gillard was given the top job in Canberra. Also last week 10 civilians, including at least five women and children, were killed in NATO airstrikes in Afghanistan’s Khost Province.

‘We have received five bodies of civilians in our provincial public hospital,’ Khost provincial health director Amirbadshah Rahmatzai Mangal told AFP.

‘The dead include two female children of seven and eight years of age.’

Those irritating Kiwis across the ditch said they wouldn’t send a soldier to Afghanistan because it wasn’t in their national interest. How dare they not play this game?

That war in Vietnam was in the 1970s, but in the 2000s they’re still trying to win hearts and minds and occasionally apologising for mistakes, like when they blast a primary school and kill a lot of kids, (although these days they’re more likely to just blame the terrsts).

Within the first 24 hours of Julia Gillard being given the hot seat in Canberra she was on the phone to Obama assuring him of our troop commitment in Afghanistan. Right after a fortnight when five young Australian men were killed there. Plus ça change.

Just like the wars, and the 1970s rockbands, I have a sneaking suspicion that the crocks are still going around as well.

On Saturday 4 September there will be a session called Living in the ’70s, featuring Francis Wheen and Frank Moorhouse. Get tickets here.

Posted in Author info

Tags: '70s, 1970s, Andrew McKenna, Karen Andrews, Matt Blackwood, MWF authors on

MWF 2010 authors on… passion

Posted by Angela Meyer (LiteraryMinded)

I’ve given MWF guests a list of 15 random topics to respond to. The idea is to entertain and introduce you, the reader, to other sides of the MWF authors and their work, which may not be revealed on festival panels. The authors were allowed to respond in any way they liked, and were given no word limits. To learn more about the authors and what they’re doing at the festival, click their names through to their MWF bios.

My passions include:

Gary Oldman & Val Kilmer; collecting ‘Old Hollywood’ themed coffee table books; second-hand bookshops; trying not to let the responsibilities of adulthood obliterate the delights and memories of my inner-child; ideas; Hamlet; Gothic Literature; a nice, long walk; coffee; sleep; Whitby Abbey, from the Dracula association (this picture hangs in my bedroom); wondering about the identity of Jack the Ripper.

There’s a scene from Robert Bresson’s film Pickpocket, which the screenwriter and director Paul Schrader quotes repeatedly in his work – but Schrader alters it.

The version in American Gigolo takes place in an official area. A woman visits a man. They’re separated by a pane of glass. The woman brings her right hand up across the line of her body, reaching forwards, and rests the outer edge of her fingers along the inside of the glass. The man leans in to press his forehead against the same point on the other side of the glass, hard. Their movements are reciprocal rather than identical. It’s the closest they’ll ever get to touching.

In Pickpocket, Bresson’s protagonists are also separated, but by bars rather than glass. They can touch, if only obliquely. She kisses his fist, which grips a bar. He presses his cheek to her temple; or rather they press together the small cross-sections of skin that can be contained within a single square of the prison grid.

In the version of the scene from Schrader’s Light Sleeper, there are no bars and no glass, and the final shot initially appears to be a still, which freezes the image of Willem Dafoe’s character kissing the hand of Susan Sarandon’s character. But even as the credits roll, even as they keep rolling, it’s only the flickering of Dafoe’s closed eyes – moving like those of a dreamer in the R.E.M. phase – that betrays the patience of both actors.

Spanish fingers pointing to their first star on World Cup winning jerseys.

This photo shows me sitting next to my first boyfriend Peter Zombory-Moldovan (on the right). I was two years old and Peter was our neighbour in Manchester, England. Apparently the two of us would kiss and hug so enthusiastically we’d tumble over onto the floor. I don’t remember loving this little boy of course, it’s all hearsay, but I have no doubt toddlers can feel as strongly for their special friends as adults do.

I was struck by Glyn Davis’s review of Tony Judt, Ill Fares the Land, in The Age (26 June 2010), which he describes as ‘a work of passion’. The comment led me to wonder what it would take for more academic writing to be passionate, committed and ‘urgent’.

Feel free to share your own responses to the topic, or to the authors’ responses, in the comments.

Posted in Author info

Tags: Carol Bacchi, Jon Walker, Karen Andrews, Matt Blackwood, passion, Sally Muirden