Blog Archives

Spreading the word: Elif Batuman and Amazon reviews

One of my favourite guests from last year’s MWF, Elif Batuman, has an addictive blog, the kind that sends you spiralling into an array of new browser tabs and furious online book-ordering.

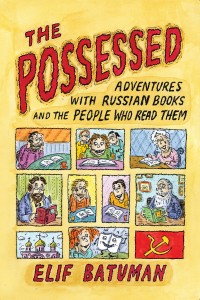

A post from a couple of months ago recorded the author’s discovery that while her book The Possessed has garnered a number of five-star ratings at Amazon, it has also earned a large number of one-star reviews. The Possessed has been received well by critics, and Batuman wondered why reader reviews were, on average, less positive, guessing

that satisfied readers of a well-reviewed book are less likely than unsatisfied readers to post on Amazon. One group thinks to itself, “Why should I write a good review when the Times already did,” while the other thinks, “Aha, a venue to express my outrage at the Times for hyping this book.” I found support for this hypothesis in the fact that many particularly well-reviewed books tended to have relatively low reader ratings. So… it’s the old dialectic of hype vs. backlash.

In response to this apparent reader proclivity, Batuman now writes five-star reviews on Amazon for books she loves. Thus far, she has lauded titles including Kazuo Ishiguro’s Nocturnes and A Fraction of the Whole by Steve Toltz, another 2010 MWF guest.

There were two things that interested me about this pro-good-book activism.

First, how much is a reader persuaded by reviews, whether print or online, by paid critic or passionate reader, to buy a book? I read criticism, in the broadsheets, in literary magazines and online, and blogs dedicated to reading, but it’s just one element in a complex algorithm, something like: [(number of times title positively covered in book press/blogs + recommendations from friends) – books bought this week] x (is it in stock at the shop + price ) / how much am I in the mood for the genre/author = likelihood of buying book. (Don’t judge my maths.)

I don’t usually buy books from Amazon, so I’m not sure how much store a reader might set by an Amazon review (though an Amazon review by Elif Batuman might be a different story to the review by XXmishOz89). And there are of course countless other places to find out if readers have liked a book, including blogs (looking forward to using this book blogs search engine, via Galleycat) and recommendation-based social networking sites like GoodReads, Shelfari and LibraryThing (which I have studiously avoided due to its name conjuring up the image of a Muppet-like monster who lurks behind the Dewey number 833.01–913 stacks).

Second, do people talk about books they love as much as books they don’t love? At my blog, I try to write something about every book I read (failing miserably these days), however much I enjoyed it. One reason I’ve slacked off so much is that I’m often loathe to add to a heap of praise – what else could I possibly say about this bestseller or that local darling?

Do you heed book reviews and reader comments when selecting something to read? And would you take to the internet to recommend beloved books to fellow readers, or are you more likely to explain why you disliked a disappointing one in an online forum?

How Russia changed their lives

I have this terrible habit of becoming interested in too many things, and ending up with massive lists to follow up on – Italian cinema, Australian authors, HBO TV series. One of these things is Russian literature. I’ve done a bit of Chekhov, I’m making my way through some Nabokov, I’ve done a little Tolstoy, a little Dostoyevsky and a little Gogol. Then I read Elif Batuman’s The Possessed (you’ll find my blurb in the Australian edition) and I was overcome with excitement for what I still have to discover.

I have this terrible habit of becoming interested in too many things, and ending up with massive lists to follow up on – Italian cinema, Australian authors, HBO TV series. One of these things is Russian literature. I’ve done a bit of Chekhov, I’m making my way through some Nabokov, I’ve done a little Tolstoy, a little Dostoyevsky and a little Gogol. Then I read Elif Batuman’s The Possessed (you’ll find my blurb in the Australian edition) and I was overcome with excitement for what I still have to discover.

Batuman as a child growing up in New Jersey was quite enchanted by the idea of Russia – a mysterious other place, a ‘wonderland’. But she was possessed by Russian literature quite by accident. The first novel she fell for was Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina – she says, ‘for the first time I had an idea of the novel that can compete with life’, that can run alongside a life. Batuman finds Russian literature richer in some ways than literature in the English or French canon – the way it can be ‘funny and sad at the same time’. Pushkin and Gogol are two of her favourites. Batuman decided to explore Russian literature as an academic, after discovering she wasn’t the kind of writer who imitated, re-enacted or re-lived the books she loved, but the kind who gets out into the world and immerses herself in ‘a metonymic, geographic way’ – like going to Tolstoy’s house, and meeting the crazy relatives of dead authors. Batuman found she enjoyed ‘going through, looking for clues to an absent person’. She added: ‘which is a lot of the time what life is like’.

Also on this panel, chaired by Judy Armstrong, were historian Sheila Fitzpatrick and author Maria Tumarkin. Tumarkin was born in the former Soviet Union, emigrated to Australia in 1989, and her book Otherland charts the journey she made back to Russia and the Ukraine with her teenage daughter. Tumarkin said she had avoided writing about Russia for years, and mentioned the fact that so many great writers only wrote insightful things about Russia after leaving. After living in Australia and inhabiting the language for a while, she then felt she could write about the place from which she came, and what was happening at the time she left. Her books are personal in style, because the journey into the past and into Russia is personal. Tumarkin didn’t want to write a journalistic book or straight historical enquiry.

Sheila Fitzpatrick grew up in Melbourne in the ’40s and ’50s, when the Soviet Union ‘wasn’t generally loved’ by most people. Her father was a socialist though, and Fitzpatrick sees her interests stemming from Cold War tensions. She wrote her final year thesis at Melbourne University on Russian music – at a time when it was difficult to get research materials. Fitzpatrick told a few stories about traveling to Russia and to Uzbeckistan in the late ’60s. ‘Unlike other people who had to get out of the Soviet Union, I had to get in’, she said. She was interested in their ‘extraordinarily uncomfortable and inconvenient everyday’. As a foreigner she was marked. The British Embassy instructed her not to make friends as ‘they’re all KGB’. The Russians, too, always thought foreigners might be spies. Fitzpatrick even started to think ‘how do I know I’m not a spy?’ Fitzpatrick is Distinguished Service Professor in Modern Russian History at the University of Chicago and an annual Visiting Professor at the University of Sydney. She has written many books on the subject.

Sheila Fitzpatrick grew up in Melbourne in the ’40s and ’50s, when the Soviet Union ‘wasn’t generally loved’ by most people. Her father was a socialist though, and Fitzpatrick sees her interests stemming from Cold War tensions. She wrote her final year thesis at Melbourne University on Russian music – at a time when it was difficult to get research materials. Fitzpatrick told a few stories about traveling to Russia and to Uzbeckistan in the late ’60s. ‘Unlike other people who had to get out of the Soviet Union, I had to get in’, she said. She was interested in their ‘extraordinarily uncomfortable and inconvenient everyday’. As a foreigner she was marked. The British Embassy instructed her not to make friends as ‘they’re all KGB’. The Russians, too, always thought foreigners might be spies. Fitzpatrick even started to think ‘how do I know I’m not a spy?’ Fitzpatrick is Distinguished Service Professor in Modern Russian History at the University of Chicago and an annual Visiting Professor at the University of Sydney. She has written many books on the subject.

After the session I realised I forgot to bring my copy of The Possessed to get signed. Never mind, the Russian lady was present at the Federation Square Book Market and I picked up Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, which I’ve always wanted to read, and Elif Batuman kindly signed it ‘Fyodor (via Elif)’ for me…